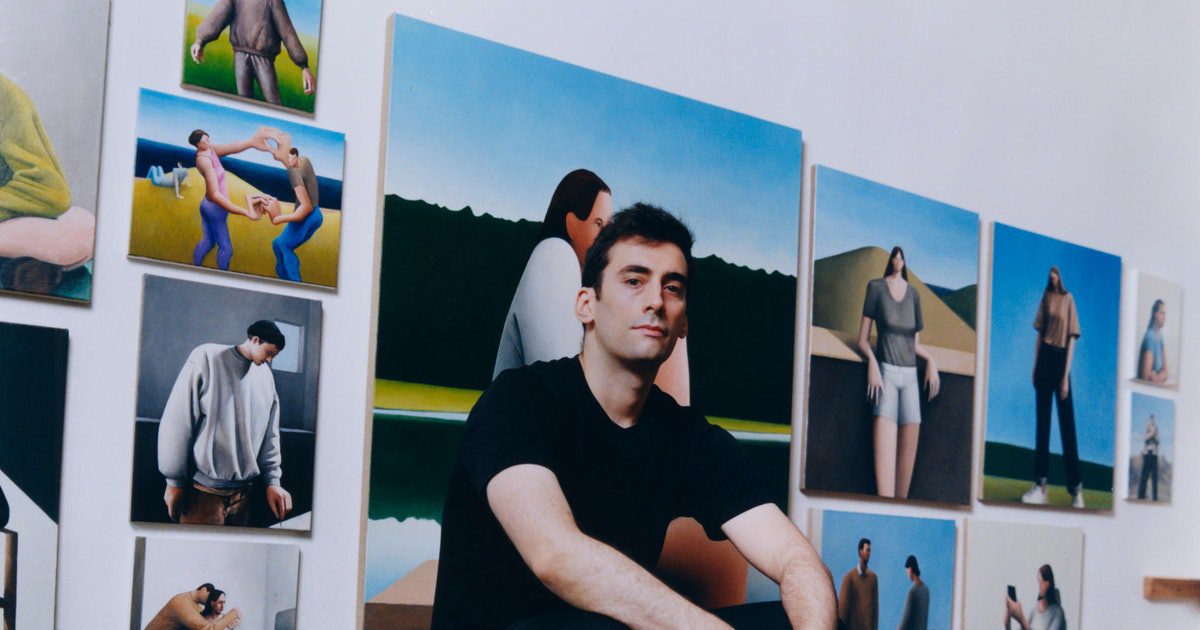

The painting that started blowing up the artist Tony Toscani’s Instagram notifications a year and a half ago depicts an anonymous, morose-looking man with a comically small head. He clutches a cup of coffee and stares into what seems like an unending abyss. I’m not at all surprised when I stop by Toscani’s studio in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, once he says that, in his mind, the man is actually staring into a computer screen. Toscani has come to think of electronic devices—as well as books and cups of coffee—as ways to express a form of personal melancholy. I’m pretty sure I had been in the same position as the figure in his painting that morning—and far too many more than I’d care to count.

Melancholy proved particularly resonant during lockdown, when it was widely shared by art followers on social media, but in fact the painting first started being circulated in 2018, following a group show at Massey Klein Gallery on New York City’s Lower East Side. Electronic devices featured prominently in Toscani’s first solo exhibition at the gallery a year later, but the painter is now working on achieving the same effect of dislocation without showing the gadgets. “She actually used to have an iPhone, but I painted it out,” Toscani says, gesturing at a just-barely visible patch near the titular figure in Woman in a Lake, the largest of his works on display in the space where he and his wife, the artist Adehla Lee, live and work. On September 3, it will become the centerpiece of Toscani’s second solo exhibition at Massey Klein, comprising what is simultaneously his most timely and timeless body of work yet.

Toscani, 35, grew up in suburban New Jersey, not far from lakeside vistas like the ones he often depicts. When he wasn’t going to punk shows in Philadelphia and New York City, he was thinking about the themes that now recur in his work—monotony and despondence most chiefly among them—but expressing them through music. He found painting to offer the same type of “visceral” experience as music when he was studying at St. Joseph’s University, outside Philadelphia; he was among eight students to graduate from its tiny fine arts department in 2009. That same year, he enrolled in the MFA program of the School of Visual Arts in New York City and started working as an art handler. His experience at Sotheby’s, in particular, ended up transforming his practice.

“One minute, you have this antiquities-era Greek head, and then you put that down and you’re running to Contemporary and hanging a Warhol for a private viewing,” Toscani recalls. He left, in 2015, with a herniated disc and an uncomfortable awareness that what he’d thought of as a scene was really an industry. “I learned a lot about the art world, and about people in general,” he says. “And I think that’s what made me really get into people more, because I had never painted them before I quit.”

Toscani means “never” in the literal sense. For a while, he says, as he started to focus on the human figure, he had no idea how to paint clothes or skin. Eventually his style evolved, via trial and error, into a kind of inversion of Fernando Botero’s round, squat figures. When he’s working on his elongated, thimble-headed portraits, Toscani places his figures on an imaginary landscape in the future, in which digital lives have replaced human interactions. “I just picture these meandering giants walking in a field, not even looking at each other,” he explains. “Our limbs growing because they still need to serve the real world functions of being a living creature—but our heads getting smaller because they’re less important.”

Like the rest of us, Toscani has had more than enough with isolation—including within his practice. The pandemic took hold just as he was getting “really hot and heavy” into depicting relationships and human interaction. “As soon as I did the last stroke,” he says, pointing to a painting that will be on view in “Isolation” that depicts a scene of a crowded Art Basel booth, “lockdown happened.” Even if Toscani could personally do without more art fairs—”just the worst,” he says, “like duty free”—he has found it difficult to make paintings depicting social life without engaging in real-life socializing. After all, artists want their work to be a conversation. As I’m leaving his studio, he says to me, “If you have any opinion or critique or anything, I’d love to hear it.” He adds, “Even years from now—just email me about it.”